Fred D Hinger | Reflections on a Great Musician

Each year when the month of February rolls around, I tend to think a lot of my relationship with one of the most musical and original minds that I have had the pleasure to know, and that is Fred D. Hinger. I suppose this is because he was born in February 1920, which means that this year (2023) he would have been one-hundred three years old had he still been with us. Wow! One-hundred three years have passed since he was born, and he has been gone twenty-two years this past January (2023).

This remarkable gentleman was my teacher at Manhattan School of Music and my mentor and friend for the remainder of his life. I feel at this time to share some reminiscences of the man we called “Mr. Hinger” while we were his students, and after we became professionals ourselves, insisted that we call him “Dan.”

A Little Background

First, a little background. Even though he was named Fred D. Hinger, he was known to family and friends as “Dan” throughout his life. The D stands for Daniel, and it differentiated him from his father, Fred G. (for George) Hinger. I remember him telling me that he was a native of Cleveland, Ohio. In addition to his musical abilities, he was mechanically inclined, and put in some time after his stint in the Navy Band working in a machine shop which produced wire. This was to stand him in good stead in later years when he manufactured his own instruments. His interest in music started in his junior high school years, where he learned to play the snare drum. This led to him developing his skills on the other percussion instruments.

After high school, he attended the Eastman School of Music where he studied percussion with the highly respected William Street and received his Bachelor’s degree in Music Education. (He told me that it was a good degree to have, as it allowed one to have extra options for a career.) The lessons with William Street had a great influence on Dan’s own musical personality, as it provided a foundation from which Dan could build his own extremely interesting and thought-provoking style. During his college years, Dan played in as many ensembles as he could, also serving as a percussionist in the Rochester Philharmonic. Playing in as many ensembles as one could was something he recommended to all his students. “Experience is the best teacher”, he reminded me on many occasions. In fact, if memory serves, I believe he even sang in a choir as he taught himself to listen to the other voices and trained his ear that way. He always insisted that singing in a choir was essential for ear training and pitch memorization (so indispensable to a timpanist) and another form of ensemble training. After graduating from Eastman, he found himself a member of the Navy Band in Washington DC, where he remained for six years, eventually becoming its xylophone soloist. I remember him telling me that prior to becoming a member of the Navy Band, he had been offered a position with the Pittsburgh Symphony (I believe it was), and that he had to turn this down as he was drafted into the Navy. Six years there certainly didn’t do him any harm, and he was able to develop his considerable mallet and percussion skills. He took his duties as xylophone soloist so seriously that he took tap dance lessons in order to strengthen his movements from one end of the keyboard to the other. It must have been quite a sight to see him play. Remembering him demonstrating to me some mallet excerpts, I got just a little taste of what his mallet skills were, and the sound he got from bells, xylophone, or marimba was extraordinary. While in the Navy Band, he met and married Margery Jean Eccles, whom he had known since childhood; she was indeed a gracious lady. They had two children, Shirley Jean, and William Daniel. After his time in the Navy was over, he returned to Cleveland where he began working on his Master’s degree at Western Reserve University. However, a situation arose in which there was a vacancy for Principal Percussion in the Philadelphia Orchestra. Benjamin Podemski was leaving the orchestra and there was an audition. Dan went and played for Eugene Ormandy. Apparently he impressed Ormandy enough to be offered the position, which he held for three seasons – 1948 to 1951. He later asked Ormandy what it was that made him offer him the position, and Ormandy apparently told him that it was the sound of his cymbal playing which impressed him. The position apparently included playing assistant timpani to David Grupp, who succeeded the late Oscar Schwar in 1946, and remained in that position until illness forced him to retire in 1951. When it was announced that David Grupp had officially retired, Dan was invited to audition for the timpanist’s position, but it was not your usual audition. Ormandy called for a rehearsal of the entire orchestra, and the timpanist’s folder was loaded with everything from Tchaikovsky’s Romeo et Juliet, Brahms 1st Symphony, Strauss’s Til Eulenspeigel to Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps. He had the orchestra and Dan play through much of the repertoire, and at the end of the rehearsal, Dan was invited to take the position on a one-year trial basis. Dan held out for a longer contract, politely arguing that since he had been filling in for Mr. Grupp for much of the previous season, his playing was a known factor. Dan won his point, and remained as timpanist for the next sixteen years, a tribute to his persistence and fearlessness. His years with the Philadelphia Orchestra are well known, with many recordings for CBS/Sony to his credit. There are quite a few recordings which enable us to sample Dan’s artistry with the orchestra.

In 1966, the orchestra had just gone through a long drawn-out labor struggle entailing a strike that lasted for several weeks. Just after that strike ended, Dan was apparently invited up to New York to talk about accepting a position as one of the two principal timpanists of the Metropolitan Opera as from the 1967-68 season. (Fred Noak, who had been one of the timpanists for many years, had passed away, thereby creating an opening.) By this time, (as he related to me), he was tired of the constant touring with the orchestra and the political side of things left him worn out and thinking it was time for a change. So, he went up there to check things out and talk with management there to see what was in the offing. I remember him telling me that he had no intention of auditioning, and that this trip was purely exploratory. As things turned out, he was treated like royalty and conditions there were so much to his liking that he was offered the position based on his reputation as a player, which was even then legendary.

It was a sea change of sorts for him, for not only was he leaving Philadelphia, his orchestra of nearly twenty years, but going to New York (a completely different life style) and a whole new type of playing and a whole new repertoire. Dan was never afraid of a challenge and after settling on a house in Leonia, New Jersey, adjusted to his new position and acquitted himself magnificently. At that time, the Met toured for six weeks at the end of the season, and while there were many out of town performances, the out of town touring was lumped into that one period instead of being spread throughout the season, which was fine with Dan. He also relished the opportunity to learn the new repertoire and over the years grew equally expert with the opera repertory as he was with orchestral.

Even though performing was his main area of musical activity, he always relished the opportunity to teach. His years as instructor at the Curtis Institute of Music, followed by his tenure at the Manhattan School of Music and Yale University School of Music gave him the scope to educate a whole generation of percussionists and a lot of satisfaction.

Dan was truly a bit of Renaissance man as well. His work in the wire factory kept him interested in mechanical things and dissatisfaction with the percussion equipment led him to experiment with different materials and eventually form his own instrument manufacturing company, known as Hinger Touch-Tone. From mallets (timpani, snare drum, and keyboard mallets) to Dresden-style timpani and the Space-Tone snare drum, he, ably assisted by his son Bill, made instruments and accessories of the highest quality.

Dan retired from the Met in 1983, and continued to teach at Yale and the Manhattan School of Music until 1989. He sold off the mallet side of his company in 1986 and closed the factory at the same time as the returns on making instruments were diminishing beyond the point of satisfaction.

He moved to Huntsville, Alabama where he spent the remaining years close to his family. He continued to teach for a while, appearing at PASIC conventions until his health declined. He passed away in January of 2001.

Recorded Legacy

When I speak of his recorded legacy, I speak of the recordings he made while he was timpanist of the Philadelphia Orchestra. He filled that position from 1951 until the fall of September, 1967, when he left to go to the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. The orchestra during this period was signed to record for Columbia Records. They had previously recorded for RCA Victor, and getting the Philadelphia Orchestra was quite the coup for Columbia Records. (This is not the same Columbia that was associated with EMI Records.) Dan made quite a few recordings with the orchestra as timpanist. I will list some of what I consider my favorite recordings, ones that feature the best of his work. Before doing so, I must caution that these recordings were made in venues that didn’t always have the best acoustics, and the recording engineers, while first rate in many ways, didn’t have access to what we have become used to in the twenty-first century. I do know that they recorded quite a bit in the Broadwood Hotel, and of course in their then home venue, the Academy of Music. Despite the acoustics, the artistry of Dan Hinger shines forth, especially after the digital re-issues. Here are a few of the recordings that I would not be without:

1. Beethoven: Ninth Symphony – Eugene Ormandy/ Philadelphia Orchestra- Mormon Tabernacle Choir

This was recorded in two different venues, if I am not mistaken. The orchestral movements (one through three) were recorded in Philadelphia, and the choral fourth movement was recorded at the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Performance styles of Beethoven have changed so much since the authentic period-instrument movement took center stage. This is old-style big-band Beethoven, and the Philadelphia Orchestra plays this music beautifully. Dan Hinger’s contributions in the scherzo (on three timpani) bring out the articulation perfectly. (Still available on CBS/Sony)

2. Bartok: Concerto for Orchestra

Nothing to worry about here regarding authenticity. Ormandy has the orchestra playing at the top of their form, and Dan is at the top of his game here. The performance all around is just great, and the Intermezzo Interotto is spot on. He nails it, in other words. Still available on Sony/CBS.

3. Richard Strauss: Death and Transfiguration

Re-released on CBS/Sony as part of the two CD set “The Great Tone Poems”, this is another stellar musical performance. Rhythmically as well as musically, his playing is spot on. I have never heard the rhythmic passages from before letter G until H played with more intensity and commitment. This work is on a CD that contains fine performances of Til Eulespiegel and Don Juan. Both are very good. Not sure if it is still available. The other disc was devoted to Strauss’s Don Quixote and Also Sprach Zarathusthra. Both are given excellent performances, and in the opening of Also Sprach Zarathusthra, Dan makes the drums sound musical as well as bringing out the power implicit in the triplets. Not an easy thing to bring off.

4. Tchaikovsky: Romeo and Juliet – Originally on a LP with the Sleeping Beauty Ballet suite, this is my all-time favorite recording of the piece. Like the Strauss works, this is played for all its worth – Ormandy is no slouch of a conductor. The phrasing and committed playing and the sound that Dan gets – his final roll is tremendous. Also, the way he phrases the heartbeats before that final roll has to be heard to be believed. On the LP, the Sleeping Beauty suite was well recorded, and can be found on its own CD. I picked up a Japanese Sony CD which had the Romeo and Juliet on it on one of my visits to Tokyo with the Oslo Philharmonic.

5. Sibelius: Symphony No. 2 & 7 – Still considered my favorite recordings of both pieces. The orchestra and Ormandy are superb, and Dan is at the top of his game on both works. Just listen to the solo B flats in the Vivacissimo – perfectly scaled in dynamics. Available on Sony/CBS.

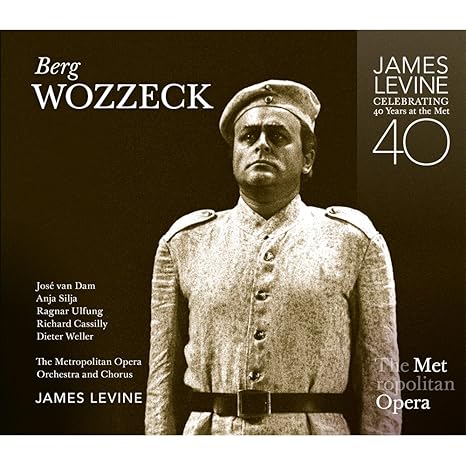

I could go on and include Rachmaninov’s 1st Symphony, Sibelius Violin Concerto with David Oistrakh, more Tchaikovsky and Richard Strauss, but you get the picture. Each of these serves as a testament to the man’s musicianship, which in my view had very few peers. Sadly, there are no recordings from his time at the Met. DGG recorded Bizet’s Carmen in 1972-73, but this was played by his colleague, Richard Horowitz. There are a few videos from his time there – most notably a Tannhauser from 1982 conducted by James Levine, and there are several shots of the man himself at work. This was briefly on YouTube before being withdrawn due to copyright infringements. Much of this legacy from this period is on tape at the New York Public Library Archives – or was when I last checked. NB! I discovered a recording of Berg’s Wozzeck with James Levine conducting the Metropolitan Opera, with Jose Van Damm in the title role. It was from an archive broadcast of March 8th, 1980, and after purchasing it from the Met Gift Shop on a recent visit to New York, discovered that Dan Hinger was the timpanist, and his playing is superlative!

This is the recording and it is available on Amazon.com.

Reminiscences

I’d like to close with a couple of reminiscences which have stayed with me all these years. One concerns his teaching environment and the other has to do with his quest for musical perfection. I know that I have shared these in earlier blog posts, but it is well worth re-sharing as they bring the flavor of the man and his musicianship back to life.

Dan did not teach at the school during my four years under his tutelage. He preferred teaching in his own private studio, which was set up in the basement of his home at 357 Hilltop Avenue in Leonia, NJ. To get to his studio, one would have to take the Number 1 Broadway Local of the IRT from the 116th Street station all the way up to 168th Street – take the elevator up to the George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal and take Public Service Bus 163 to Fort Lee/Hackensack. One would ride that all the way across the bridge into and past Fort Lee, and disembark at Glenwood Avenue in Leonia. One would then walk two or three blocks north on Glenwood, then turn right on Hilltop and walk up the hill. His house was on the left – you could enter his studio through the garage – on many a day Dan would be waiting for you at the open garage and direct you inside himself, or if he was working with a student, you’d go to the front door and wait in their living room. Dan’s wife Jean would greet you and direct you to the living room sofa to wait your turn. When the previous lesson was finished, Dan would come up and greet you with a little small talk – not much and then direct you to the studio.

The Studio

Since I was to spend a lot f time over the next four school years taking lessons from one of the greatest musical minds in the classical percussion world, a brief description of the studio is in order. I mentioned earlier that it was in the basement of his house. It was a space about twenty-six feet in length by about thirteen feet in width and had a stairway that led up into the house and a door to the garage at the rear. It had a pair of sliding doors that led into his yard, and a thin row of windows in the wall above where the timpani were situated. The room contained a full set of timpani – the two inner drums were of the Dresden pedal variety – and the outer drums were generally of the Anheier-cable type, although they were fabricated by Dan. When I started lessons on a full time basis in the fall of 1971, he had a pair of older Light Dresdens – what we would call Mark XIs as the inner drums. These timpani were more than a cut above the school’s Ludwigs. They had calfskin heads. Other than a quick glimpse of calfskin on a set of Ludwig timpani at West Point back in 1965, this was the first time I would work with calf skin. The timpani were set up against the south wall – there was a music stand in between the inner drums, and another music stand set up as a trap table to the left – this is where we’d put our mallets during our lessons – or he’d have some mallets there for testing and for us to try out. His collection of recordings and record player – this was in the days of the vinyl LP – were off to the left in the corner –and there was sufficient space for him to stand beside us and do his teaching. Behind the timpani and further away from the south wall was a beautiful Deagan marimba which he used for mallet lessons. Like his timpani, he kept this instrument in tip-top shape. A music stand stood behind the marimba, and to the left of it, but out of the way enough to allow one to get back and forth from marimba and timpani was the oddest looking snare drum I had ever seen. It had a shell made of cast iron, with gut snares and Remo Ambassador heads. The drum itself weighed approximately twenty-five pounds, but it sounded unlike any snare drum that I had ever heard. There were several cabinets full of music in the rear of the studio, and the walls of the studio were paneled. There were also pictures of conductors (autographed) on a couple of the walls. The tile floor was covered by several small rugs. This was Dan’s workshop, and I can understand why he preferred to teach here. Admittedly, it was inconvenient for the student as it took ninety minutes at a minimum to get there from MSM, and there was always the return trip. I made sure that most of my lessons were scheduled in such a way that I did not return to MSM – but went right on to Times Square where I caught the bus home. I didn’t always have to take the bus to Leonia. Whenever Dan had a rehearsal that went overtime or a lesson was scheduled just after a rehearsal ended, he would have me meet him at the Met, and he’d drive me to his home in his white 1968 Volkswagen “beetle”. He was a bit of a cowboy when it came to driving, and I felt that I took my life in my hands whenever I drove with him, but I sensed that he knew how far he could push the envelope and we always arrived at his house without incident, sharing small talk on the way.

One thing I learned early on – never be late for a lesson! There was one occasion in the middle of my sophomore year when I missed the #163 bus by a minute – I reached the platform just as it was pulling out! The next one wasn’t for a half hour, and this was not the era of the cell phone in which one could call ahead and let the teacher know if you were going to be late, not that this would have made a difference. As it was, I was a half hour late getting there, and Dan, though always the gentleman was not a happy camper. He chewed me out in a quiet but at the same time quite decisive manner. I tried to explain out the missed bus and slow train, but he was not having any of it. I was frustrated beyond words and he must have sensed it, because he immediately explained his point in a gentler manner. His point was that if this had been a job, I would have been fired. He counseled me to always leave extra early in order to avoid these kinds of situations. “Better early than late” has been my motto ever since.

This next reminiscence has reference to his musical style and speaks volumes regarding his passion for music and his zest. His approach was different from the normal J-stroke in that with his method one pulled the sound out of the instrument – it somewhat eliminated the extra motion of what I call the attack and emphasized the heart of the stroke, which he called the touch as well of the follow through. The sound of the drum – to my ears at any rate – was much more musical. It allowed the drum to sing rather than to bark.

This approach carried over to the mallets and snare drum as well.

He was tireless in making sure his students understand the essence of what he was teaching, and he would get really excited and his eyes would light up and he would say “That’s it –that’s it!” when you showed by some fine playing that you “got “it. Conversely, when one performed poorly or did not get a good sound – he suffered. I remember one time, in working on the slow movement of Beethoven’s Third Symphony – the “Marche funebre” – I landed too hard on a low G roll – the initial attack was a little too hard for his liking – and he let out a wail of desperation – Nooooooooooo!…. so loud that it could be heard upstairs by other students waiting their turn for a lesson, and could probably be heard all the way to Glenwood Avenue.

I was mortified at making such an egregious error and eliciting such a decidedly negative response from my teacher. However, that response lasted only for a minute – he quickly put me to rights and set me straight as to how this symphony should sound. (This was one of his favorites.)

In conclusion

I was most fortunate to be student of this musical dynamo and am grateful that our relationship continued after I had finished my studies with him. He was responsible for bringing me to the attention of the Oslo Philharmonic and continued his moral support throughout my tenure and beyond. For this, my life is the richer.

Here is a link to the Intermezzo Interroto from the Concerto for Orchestra of Bela Bartok:

Here is the link to the Scherzo of Beethoven’s Ninth:

And a bonus – the link to movement one of the Franck D minor Symphony:

And a super bonus! Sibelius: Symphony No. 2!

Enjoy!

Recent Comments