The EMI Recordings 1987-1997| Part Three

Pokofiev –Mussorgsky –Dvorak

The previous two blog posts in this particular series were devotes to the first three recordings that we made for EMI – namely our Tchaikovsky 1812/Romeo/Francesca recording, which was the first in the series, followed in quick succession by the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, and by the two symphonies of Johan Svendsen.

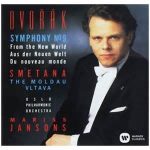

The year 1988 saw another series of three recordings : January saw the sessions for the two suites from Serge Prokofiev’s ballet “Romeo and Juliet”; August was the month we recorded our Mussorgsky disc, which included “Pictures at an Exhibition” in the orchestration by Maurice Ravel; “Night on Bald Mountain” and the Prelude to “Khovanschina”, both in the orchestrations by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov; and November, which saw the sessions for Dvorak’s “New World Symphony”, with Bedrich Smetana’s “Molday” as a filler.

Each recording session had its interesting points. I always enjoyed talking to the recording engineers and producers, and EMI had a very good crew. Our first recordings were presided over by David Murray, a very fine recording producer, and he was ably assisted by Mike Clements on these early recordings. David was a fine gentleman and very good at his business. I imagine that he found the acoustics of the Oslo Konserthus a bit of a challenge. Fortunately, they had the advantage of being ably assisted by our very good NRK recording staff, who were intimately familiar with the quirks of our concert venue.

Mike Cements was actually subcontracted by EMI, rather than a regular employee. He had his own firm, which I believe was called Black Earth, and he worked as a free-lance engineer. He was most interesting, and extremely knowledgeable. He had recorded many of the great names in classical music, as had avid Murray, and it was always fun to “gossip” a little.These two gentlemen guided our first few recording ventures for EMI. Eventually, John Fraser took over the producer’s role, and other engineers were recruited, as both David Murray and Mike Clements were busy elsewhere.

About the Prokodiev…..

I believe I had covered our Prokofiev sessions (held in January of 1988) in an earlier post, but let me mention a few brief afterthoughts I have had since then. These sessions were the first time I had used calfskin on the timpani with the Oslo Philharmonic. The calfskins I had procured from American Rawhide (formerly Amrawco), which was owned an d run by Steve Polansky. I picked these up while on tour in Chicago, and the cadmium flesh hoops I got from Dan Hinger, at the tail end of the trip.

When I had returned to Oslo, I used the Christmas break to mount the heads and put them on three drums: the middle two Hinger timpani (25” and 28”) and the 31” Light Continental chain timapno (which the orchestra still owns and has in its possession).

It was a different sound and feel than I was used too with the Remo plastic, but I have to say it was a noticeable improvement over the plastic.

The Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet Suites 1 and 2, while great music (and the whole ballet is one of my favorite pieces to play and listen to) were, alas, not in my opinion, the best pieces to start out recording on calf. Any of you will think me odd when I say that, but the music is angular in places, rhythmic and requiring hard mallets and a degree of articulation in most situations. In other words, t a lot of round, warm, legato passages. Another challenge was the extremely quirky acoustics of the Oslo Konserthus, which lacked any sort of bass response. As the hall was built in the shape of a prism, and not of a shoebox (visual aesthetics took precedence over acoustics – the hall is visually beautiful), and as there is no proscenium, and the choral section lies behind and above the orchestra), the only instruments of the orchestra that benefited from this were the violins, trumpets, and piccolo. Any instruments from midrange to bass were (and still are) at a disadvantage. I had to use larger shaft mallets (Hinger aluminum and wood; also custom-made bamboo) on order to be heard, and the same went for my assistant, and any colleagues from visiting orchestras. We had, in my assistant’s words, to “play like beasts.”

Needless to say, in recording, I had to lighten up in recording, and to play more edgier and articulate, which made for a thinner sound. When I first heard the completed recording of the Prokofiev, I admired the orchestra’s playing, but was not satisfied with the sound of the timpani. While I played the part well, I felt that the bass response was a bit lacking, and I blamed much of that on the so-called acoustics of the hall ( a point later confirmed by our producer and recording engineer).

After listening to the recording again many years later, my perspective has changed a bit, and it sounds pretty god, but I still would have liked more bass.

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibtion

When it came time to record Mussorgksy’s Pictures at an Exhibtion in August 1988, I had had more time to work with calfskin, and had put calf on all the Hinger drums. I used the Amrawco heads on the timpani until June 1988, when I met up with Bernhard Kolberg. He made a visit to Oslo and introduced himself to my colleagues and myself, and had driven a van of his percussion instruments and stands for us to look at. A month or so before his visit, I had sent our flesh hoops to him (I had heard good things about his work from colleagues) to have re-done and have Kalfo skins mounted on them. The skins were actually from Ireland (Mr. Hinger loved those heads) and I was curious to see if there was a difference between the Amrawco and the Kalfo. I can tell you here was a world of difference. While the Amrawco heads were good, the quality varied from skin to skin. None of them were bad, but then again, none of them were outstanding, although the larger heads were very good, while the smaller heads were only so-so in comparison.

The Kalfos were great in all sizes. They gave a warmth of sound lacking in plastic (as all good calfskin does) and were a joy to use.

As I said earlier, it was decided that we’d record Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition in the orchestration by Maurice Ravel; the prelude to his opera “Khovanschina”; and the “Night on Bald Mountain (sometimes called Bare Mountain) in the orchestration by Rimsky-Korsakov. If memory serves, this was the first recording to be under the supervision of the man who became our permanent MI recording producer, a Scotsman called John Fraser. John was a gentleman in every way, and a delight to work with and talk to. Musically adept (he was also an arranger and composer of note), he did his best in cooperation with the various sound engineers, both from EMI and NRK to produce as good a recording sound, which, considering the problematic acoustics of our recording venue, is saying a lot.

I treated each work differently, when it came to stick choice. The Hinger drums were used throughout. For “Pictures”, I generally used four pairs of mallets – ranging from general to hard. The hard mallets I used in the “Hut of the Baba-Yaga” – medium hard for “Gnomus” and ”Bydlo”, and rounder, general mallets for the “Great Gate of Kiev.” I preferred then, and still prefer, a round, full sound for that glorious final movement, which is one of my favorite moments. The recording went very well and Mariss and the engineers and producer were pleased with our efforts. The only ting I would change if I could go back in time was to have another Hinger 25 inch for the e in Bydlo – the 22and a half inch doesn’t have the body that the d-sharp on the main 25 inch. Either that or pedal it, but I wasn’t that courageous at the time.

Next up was “Night on Bald Mountain.” I was very much inspired by the recording of the same work made by the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy in the 1960s, when my mentor, Fred Hinger was its timpanist. It still is a great recording, and I pretty much followed in his footsteps by playing the bass line and adding a G# (pedaled on the 32 inch) along with the basses near the beginning of the piece. You timpanists will know where it is. Perhaps you have done so yourselves. For this work, I used a pair of Hinger Touch-Tone mallets (medium-hard), which were a little shorter than the normal Hinger mallets. I was given these by Dan, who told me that he used these on many recordings, and encouraged me to do the same. I kept these for years as my “lucky charm” mallets, and I used them on many occasions. They stood me in good stead, and I was satisfied with the results. The last piece to be recorded was the Prelude to”Khovanschina”. There is not a lot a lot of timpani here, but a long roll on C sharp – performed on the 28 inch timpani with a pair of medium mallets – I believe I used Feldman mediums for this- did the trick. It was a most interesting set of recording sessions.

Here is a link to our recording of Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain.” Enjoy!

Dvorak’s New World Symphony

Recording sessions for the Mussorgsky were held in August of 1988, just at the beginning of the season. Sessions for the Dvorak were scheduled for November, just before of Japan tour. As a filler for the Dvorak, it was decided that we would record the second of six tone poems from the cycle of six tone poems “Ma Vlast”, by Bedrich Smetana. This is the most well known of the set, “The Moldau”, or “Vlatava” as it is known in the Czech language.

I was very much looking forward to recording both works, especially the Dvorak, which has its challenges, and the Smetana, with which I was familiar from having played it on several occasions previously.

A dose of reality…and a quick fix

At this point, I was using the Hinger drums almost exclusively, especially since I had put the Kalfo heads on the drums. I was reveling in the experience, going through the sessions for the Mussorgsky and the concerts just prior to the Dvorak sessions, when something brought me up short on the day of the first recording session. I discovered that there was a small hole in the 25 inch head – not very big, just the size of half of a finger nail – and it was not too close to the playing surface. It was a complete mystery to me as to how it got there. I discovered it half an hour before beginning the first session, in which we were to lay down the first movement of the symphony. I didn’t have much time. I tested the drum for tone – no real problem – the head still “sang”. As I did not want to the hole to widen, I decided on a temporary quick fix. I applied a small piece of 3M Teflon tape – a very small piece – to cover the hole, and the Good Lord must have been with me, because it worked. The head held through all the sessions, and the tone quality was more than acceptable.

When it came to actually recording the symphony, the usual challenges presented themselves – articulation and balance. For the opening of the symphony, I used a pair of Feldman reds – Mariss wanted the opening to be full, yet articulate. The 5/8 “ diameter shafts gave it weight, and the red felt provided enough articulation. I played the solo without the tie – articulated, as most players do. I had considered playing the tie on the B, as Szell had Cloyd Duff do, and as Cloyd himself preferred, but Mariss wanted all the articulation, so that was the way that went down. I played on many occasions, and the articulations always won out. Since both the 25 and 28 inch drums are involved here, I was particularly anxious about the “quick fix” on the 25 inch, but I can safely report that both drums sounded good at that point, and after hearing the result on one of the listening breaks, I stopped worrying.

The second movement was relatively easy to execute – a pair of Feldman medium-soft ball mallets were the mallets of choice for this, one of my all-time favorite moments in music. Let me digress for a moment. The Dvorak New World is one of those pieces that when one sees it scheduled for the coming season (much the same happens with Tchaikovsky 4), one sighs and says to oneself “Not again!” However, when one actually gets to play it, one re-discovers just how beautiful and fun to play the work is the same applies to the Tchaikovsky. I really enjoyed breathing along with the brass during that second movement. And I loved Håvard Nårang’s exquisite English horn solo. It is one f the highlights of the recording. It was also a nice breather from using harder mallets.

The third movement is perhaps the trickiest of the four. Hard mallets are required throughout. I used the Feldman blues with a half-inch shaft, and found them just right for this movement.

This is perhaps the trickiest movement in the symphony. It moves fast, and there are many changes of tempi and mood. One has to be on top of his game to do the movement justice. While the rhythms are not by themselves complex by any stretch of the imagination, it is the change of tempi and mood that present the player with the challenge. The music is fleet of foot in the scherzo section, and gentle in the trio.

The trio also requires sensitivity in dynamic gradation. I speak of the G-c interjections. They must be clear, articulate, yet nuanced, and never too prominent. The blue Feldmans (1/2 inch shaft) and a pair of yellow medium mallets made by Dan Haskins got me safely through that movement for our recording sessions.

The last movement is fairly straightforward, and a pair of general purpose mallets (with a pair of medium hard mallets for a couple of spots) will do the trick. The sessions were basically without incident and the results were to my mind, quite satisfactory.

Listening to the recording after twenty-nine years, I actually enjoy listening to it more now, then when it was first released.

Here is a link to our recording of the Scherzo of the “New World Symphony.” Enjoy!

Recent Comments